Article

December 2023 Sprouts

Most dligent changemakers,

We often talk about our work at Growing Hope as it relates to creating systemic change. But what is systemic change? How does one organization in Ypsilanti enact meaningful, systemic change?

On November 5th, I was honored to join more than 50 BIPOC organizers, advocates, community leaders, and allies who gathered virtually with the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Ms. Ashwini K.P. A small group of us were asked to provide a brief oral testimony of our experiences of racial injustice as we work towards food sovereignty and face chronic food insecurity and food apartheid.

Our collective voice moves mountains.

Collaborating with folks around the country is awe-inspiring. I’m proud to be a part of this community alongside every one of you and have the opportunity to amplify our collective voice to enact systemic change. Online, you can find a summary of recommendations and Ms. Ashwini’s end-of-visit report, and I’ve included a snippet of my testimony below.

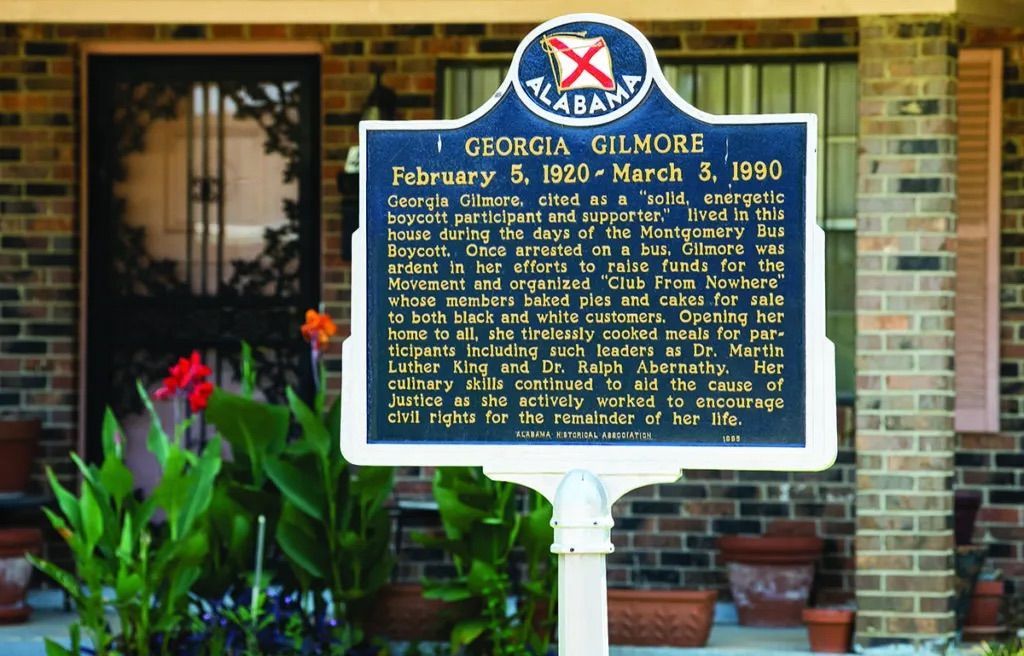

Land access is consistently the number one barrier to business development or ensuring a right to food for growers across our country. For growers of color, this disparity is magnified. I’m sure many of us know the national statistics that begin with stripping Black farmers of over 13 million acres of land and restricting them from federal resources for decades. This is a history that has led to redlining and apartheid that impacts every black grower today.

This week, I spoke with a Black farmer who has been farming on what has traditionally been Black land in a rural part of our community for the better part of a decade. He shared that it’s not uncommon for him to experience no warrant raids from police and threats of armed violence from nearby White residents. Because of this, many land-insecure Black farmers are being all but forced out of rural, resource-rich areas and closer to urban spaces where access to land is even more sparse.

Race uniquely affects urban growers. In cities where black and brown residents congregate, most with the most significant population, local governments use zoning and ordinances to control further how the already limited land can be used. In Ypsilanti, nearly two-thirds of all residential land is owned by just a few White property owners, and much of the remaining land is zoned in ways in which growing for production is unlawful.

In urban systems like these, I know of numerous landless farmers growing in parks and backyards spread across the region. For most growers who want to grow for themselves and their neighbors or families, there are limited ways to access any land to grow food. We work towards solutions to these barriers, such as community gardens, updated zoning and ordinances to support a right to garden, basing our food policy on the right to food, building growing commons, resource and skill sharing, and building home gardens.

There is an intrinsic connection between a right to garden and the right to food. If we can equip our community with the tools, resources, and land to grow for themselves and one another, we’ll collectively ensure fresh, local, and culturally appropriate produce for all.

Thank you for being a part of this movement.

In solidarity,

Julius

share this

Related Articles

Related Articles

STAY UP TO DATE

GET PATH'S LATEST

Receive bi-weekly updates from the church, and get a heads up on upcoming events.

Contact Us